Understanding the Mosquito Life Cycle

The animal that kills the most people every year is not a species of venomous snake, nor a giant man-eating crocodile, but is instead the ubiquitous and pesky mosquito. These tiny airborne blood suckers spread diseases that infect 700 million people every year and have caused untold suffering throughout human history.

This makes mosquitos our most dangerous enemy – and it is always good practice to better understand your enemies. This article will take a closer look at the mosquito life cycle, and hopefully give you some ideas on how to better control mosquito populations around your home and keep your family safe.

Types of Mosquitoes

Once thoroughly slapped, all mosquitoes tend to look about the same: a reddish splotch with bits of legs and wings. However, if you were to study mosquitoes (and thankfully some intrepid scientists have already done this for us) you’d see that there are actually thousands of species of mosquitoes.

In the American southeast we only have 64 different species, of which only half feed on mammals. If you’ve been bitten by a mosquito in South Carolina, odds are it was one of these four species:

Aedes albopictus (Tiger Mosquito)

These mosquitoes have prominent white stripes on their legs and a single white stripe running from head to tail on their back. Unlike most native species of mosquitoes, these invasive imports feed even during the heat of the day.

These mosquitoes can lay their eggs in tiny basins of standing water. This can be particularly problematic in habitats where cup-like vegetation and tree holes exist as natural water sources.

Aedes aegypti (Yellow Fever Mosquito)

Like the Tiger Mosquito, A. aegypti has white striped limbs, and can be told apart from its distant relative by its white lyre shaped markings on its back. As its name suggests, this mosquito is known for spreading yellow fever – although it is not the only species able to do so, and it is able to spread other diseases like Zika virus and Dengue fever.

Anopheles quadrimaculatus (Quads Mosquito)

This species of mosquito is a native to the United States, but that doesn’t make it any less annoying! Called the quads mosquito for the four spots that can be seen on its wings, this mosquito is known to spread West Nile virus, malaria, and heartworm.

Culex quinquefasciatus (Southern House Mosquito)

These small to medium sized brown mosquitoes picked up their common name from their habit of entering our homes in search of a blood meal. Typically they prefer to breed in warm, dirty, stagnant water and can spread diseases like West Nile, malaria, and Saint Louis encephalitis virus.

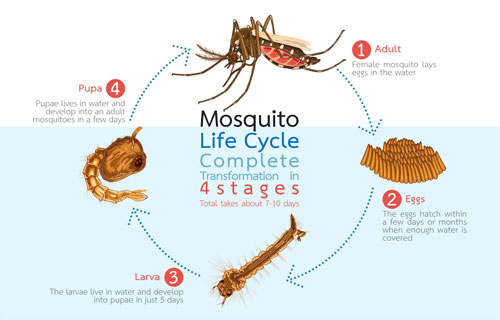

The Mosquito Life Cycle

Mosquito Egg Stage

Mosquito eggs and egg laying habits are diverse, but there are three main strategies that mosquitoes use:

Rafts

Rafts are just what they sound like: eggs are laid in tight clusters that float around like little boats until the larvae hatch and wriggle free. The Southern House mosquito uses this strategy and can lay up to five rafts in her lifetime, each containing upwards of 1000 eggs.

Floats

Like rafts, floats are laid directly on the water, but the eggs are either disconnected or only loosely connected to one another. This is an egg laying method commonly found in the Anopheles family.

Shore / Surface Eggs

Some mosquitoes don’t lay their eggs in water at all! Instead, they lay their eggs on land that is likely to be inundated with floodwaters and the eggs will remain dormant until conditions are right. This strategy is commonly employed by Aedes mosquitoes.

Larval Stage of Mosquitoes (Wigglers)

Mosquito larvae, known as wigglers, are aquatic – and spend their lives either free swimming or attached to vegetation. The larvae molt several times, moving through distinct stages known as instars, before they are ready to pupate.

While they live in the water, they must have access to the surface in order to breathe. Some species use a snorkel-like siphon to breathe, allowing them to suspend themselves vertically in the water, while others without snorkels must lay horizontally under the surface of the water in order to get their air.

Pupal Stage (Tumblers)

In order to transition from aquatic larvae to flying adults, mosquitoes must first pupate. This process is very similar to the transition that caterpillars go through on their way to becoming butterflies. Unlike butterfly pupae, mosquito pupae are motile. While they do not feed during this stage, they are able to detect and respond to motion and changes in light.

Due to their somewhat chaotic style of motion, this stage is often referred to as tumblers.

The Adult Mosquito Stage

This stage of the mosquito life cycle is the one we’re most familiar with. Both male and females drink plant nectar, although for male mosquitoes it is their only source of nourishment. Female mosquitoes must have a blood meal in order to get the protein they require to lay their eggs.

Factors Influencing the Mosquito Life Cycle

Several factors influence the mosquito life cycle and can include temperature, humidity, rainfall, and the presence of food. Lower temperatures usually result in slower development, with high water temperatures often accelerating the transition from egg to adult by several days or even weeks.

For the Tiger Mosquito, ideal conditions can mean that a freshly hatched larvae can progress to adulthood in as few as 4 days. If food is scarce and temperatures are cooler, this process can take up to 42 days!

Due to this temperature dependence, it is common to see milder winters result in much higher springtime mosquito populations. Mosquitoes are able to overwinter even through harsh freezes, but until temperatures warm up their larvae develop extremely slowly.

The Lifespan of Mosquitoes

The lifespan of a mosquito varies widely by species, and even within species due to environmental conditions. Some species’ adult forms are very short lived, with the adult stage lasting as little as four days, but two to four weeks is more typical.

Controlling Mosquito Populations

Perhaps the most important mosquito control step you can take is eliminating their breeding sites. Any source of standing water that is allowed to remain for four days or more is a potential breeding ground. Even surprisingly small sources of water like the base around potted plants can be the birthplace of hundreds or even thousands of new mosquitoes!

While removing standing water can be as easy as discarding old tires or draining unused pots, ponds, lakes, and drainage ditches will always pose a problem. In these cases your best approach is to hire a local pest control professional. These professionals have access to the right sort of pesticides and specialized equipment to apply it as an even mist over a large area.

Conclusion

Mosquitoes have been a source of annoyance and suffering for millenia, but by understanding them we are better able to control them. As our climate gets warmer, we can expect their life cycle to speed up – making mosquito control more important than ever.

Keep in mind that mosquito bites are more than just a nuisance, and can potentially pose a serious health risk. Removing standing water is the most important step towards preventing mosquito bites, but this strategy works best in combination with regular mosquito control treatments.

Understanding the Mosquito Life Cycle in North Carolina and South Carolina

Protecting North Carolina and South Carolina